Teaching

|

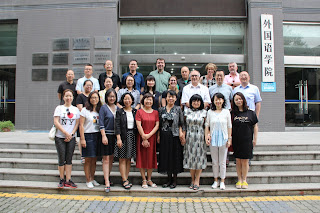

| The English Dept: Chinese and Foreign Teachers |

Teaching started up at the beginning of the week. We started with a faculty meeting on Saturday…yes,

Saturday. Weekends don’t seem to have a

lot of meaning here!

In the meeting, we went around the room and introduced

ourselves. There are approximately 20-25

Chinese teachers and 5 non-Chinese teachers.

Three of the foreign teachers have been here for 2-3 years. All three of

them were educated at Cambridge. This isn’t

that surprising, because the app that I used to get the job was a UK app. One of the teachers has been working at

Jiaotong in the summer program. She just

completed her MA at Colorado State and is here for the full year with her

Columbian husband, a doctor who will also be teaching in the med school. Dave and I are the only brand-new-to-Jiaotong

teachers. All of this is

comforting. It seems as though people

like it enough to come back.

|

| The international teachers |

The meeting started with rules… which were different from

rules that I’ve been given in other teaching gigs:

“Most Important Rule

to Remember and Follow: When

teaching at Chinese universities, foreign teachers must obey Chinese laws. Foreign teachers must know that the

Constitution of China clearly states that China is a socialist country under

the leadership of the Communist Party of China.

Therefore what they teach in their classes must be in line with the

requirements of the Communist Party of China.

Specifically foreign teachers must not spread religious ideas to Chinese

students. They are strictly forbidden to

try to convert Chinese students into followers of whatever religions.”

Ok. Fair enough. Duly noted.

Studying Chinese history, I can see why this is first and foremost the University’s

guiding rule for foreigners. Every

revolution in Chinese History, for the last 5000 years, started with a leader

who portrayed himself as a Messiah of some sort. The entire history is punctuated by this sort

of chaos and disruption initiated by a renegade religious leader. Happily, this isn’t my game, so we’re good.

The next set of rules were more pragmatic:

“Class will start and end on time. No letting students out early!”

And

“In line with the regulations of the University, all

teachers, must focus on their teaching in their classes. They should not do things that are irrelevant

to their teaching in class, such as using their mobile phones to call others

people.”

We were informed that if any of these rules were broken, we

would be involved in a “teaching accident,” which, although a lovely euphemism,

was clearly not something that we wanted to have happen. They made it clear that it would involve a

bureaucratic mess that would entangle us, the department, our Chairs and the

heads of the university. (Dave and I’ve been joking all week: Oh

no! Looks like a Teaching Accident in

the making. )

|

| Teaching Accident? |

Joking aside, I

actually almost had a teaching accident on the first day. Dave taught his class, went off to the Café

to plan his next class. However, what he

didn’t realize was, through the evil lock… see early post… he double bolted me into the apartment. When I was ready to teach my afternoon class,

I tried to leave and found that I was again a prisoner of the

apartment. See below my panicked WeChat

messages. Dave got my messages and came

and freed me.

Teaching Accident averted!

* * *

To return to the first faculty meeting: When we went around the room, the Chinese

were super gracious. One, in

particular, Doris, who was head of the School for Translation, spoke of how

lucky they were to have Dave in their midst.

“He is a precious gift to our School of Translation,” she said. (That has become another joke between Dave

and me. Whenever one of us does

something well, we say, “You are a precious gift!” You

freed me from my apartment. You are a

precious gift. You made a delicious

dinner. You are a precious gift!)

I think that the way she wants to use him is to have him

deliver medical talks to the medical school.

Her students will practice translating the technical medical terms so

that they can become valuable translators around China. It’s very clear that Jiaotong University,

which is one of the C9, or top 9 schools in China, is competing to attract

academic conferences. Having technical skilled translators will help them on

that front.

So, what are we teaching?

|

| The beginning of my Am Lit class |

Dave’s schedule will be a lot of

lecturing, reading and talking at the med school so that the translators can

practice their medical English. He also

teaches one class, twice a week, on English conversation. He is team-teaching with another Chinese

teacher, so the topics are pre-set.

First week was Jobs and Occupations. Next week is Art and Aesthetics, which

is kind of a random order, but undoubtedly will provoke interesting conversations.

My schedule is pretty

heavy. I teaching Advanced Writing to 4

classes of majors for 12 weeks. Advanced

writing to 2 classes of minors for 7 weeks.

I also teach the second half of an American Lit classes for 10 weeks,

starting mid-October (With this funky

schedule at all different times and with all different intervals, a teaching

accident is bound to happen!)

The pace of the classes is a little bit off. I meet with each of my writing classes once

a week for two hours. Dave meets

with his only conversation class twice a week for two hours. This helps us know how the administration prioritizes English-learning. Clearly, as a curriculum, conversation

is prioritized over writing. This makes sense. Speaking is crucial for these students. At the same time, once a week for a writing

class is a hard way to learn writing! We

meet for one Intensive two hour class – and nothing for a week. (A typical American class meets 3-4 times/

week for 1 to 1.5 hours, each class meeting.

That gives the student a chance to learn, practice and check what they

learned during the week.)

My plan is to introduce them to writing structures, but not

do an insane amount of writing out of class. I know that this is a sacrilege to my writing

teacher/friends. But, for me, this is

self-preservation. There is no way I can

grade papers in China the way that I graded them in the US for the number of

students that I have. In-class peer-editing

and self-evaluation will also be key.

I actually suspect that this curriculum highlights the

talents and shortcomings of our students.

They are extremely talented at learning quickly and broadly. They struggle with any sort of depth or using

what they’ve learned in a different context.

For example, they all say that they have a broad vocabulary base, which

is very true. However what this means

is, for the past 8 years they were given sheets of 50 or more vocabulary words

that they were expected to memorize for a matching test at the end of the

week. That, they can do well. But, using the vocabulary later in a

conversation or essay? There is the

rub. When I asked them in class to write

– short answer – what their strengths and weaknesses are in writing, here is a

sample of what I got:

“My writing strengths

is quickly brainstorm for ideas. However

my writing weaknesses are that firstly, I don’t know how to organize my

passage. Secondly I don’t know how to

expand my ideas except using exemplification.

Thirdly, I’m not able to use accurate word when describing

situations. Lastly, I make mistakes all

the time, especially about grammar and words spelling.”

“Strengths: I can figure out and write different types of

articles. Most time I write fast. I don’t have the trouble of worrying what to

write about. Weaknesses: Sometimes I can’t express myself

clearly. I’m not good at grammar. I don’t have much vocabulary accumulations.”

“I like writing the

details. For example, the color, the

outside or the inside. I can’t write a

very long essay. My imagination is not

good enough. And my word-choice is not

so bountiful.”

And the student of very few words:

For strengths,

she writes: “I can use proper word.”

For weaknesses: “Grammar

[then a large blank space on her page]

[followed by] Matching

together.”

Not sure what that means, but to reassure her -- no worries

there! We’ll do precious little

“matching together” in our class!

Finally: One might

wonder how the university would know if I used my phone in class, or didn’t

start class on time. Another

disconcerting part of this gig. It is very, very clear that we are being

watched. Note the cool camera, circled

in red, below. I’ll likely write more

about surveillance in China, later. But

for now, trust me. I’ll start class on time. No religious conversion. No cell phones. Communist Constitution is my guiding

doctrine!

Glad to hear teaching accidents will be at a minimum, you precious gift!

ReplyDeleteHaHa! We'll do our best... :-)

DeleteLaughing with you, precious gift. Enjoying your blog.

ReplyDeleteThanks! We're really struggling with connectivity, so the blog seems to be the only way I can hear from you all -- so really appreciate the comments :-)

Deleteoooohhhh, thank you for those descriptions! Particularly the writing examples... is THIS being monitored, I wonder????

ReplyDeleteI'm operating on the assumption that EVERYTHING is being monitored. It's likely that my life is so dull the person who drew me is longing for someone else... :-)

Delete